PTSD Service Dog vs Emotional Support Dog: Why Tasks Matter (And What Counts as a Task)

If you’ve ever felt overwhelmed in public and thought, “If my dog could just help me through this moment,” you’re not alone. PTSD changes how your nervous system moves through the world. Crowds, noise, tight spaces, people standing too close, sudden movement—things that look “normal” to others can feel like your body is bracing for impact.

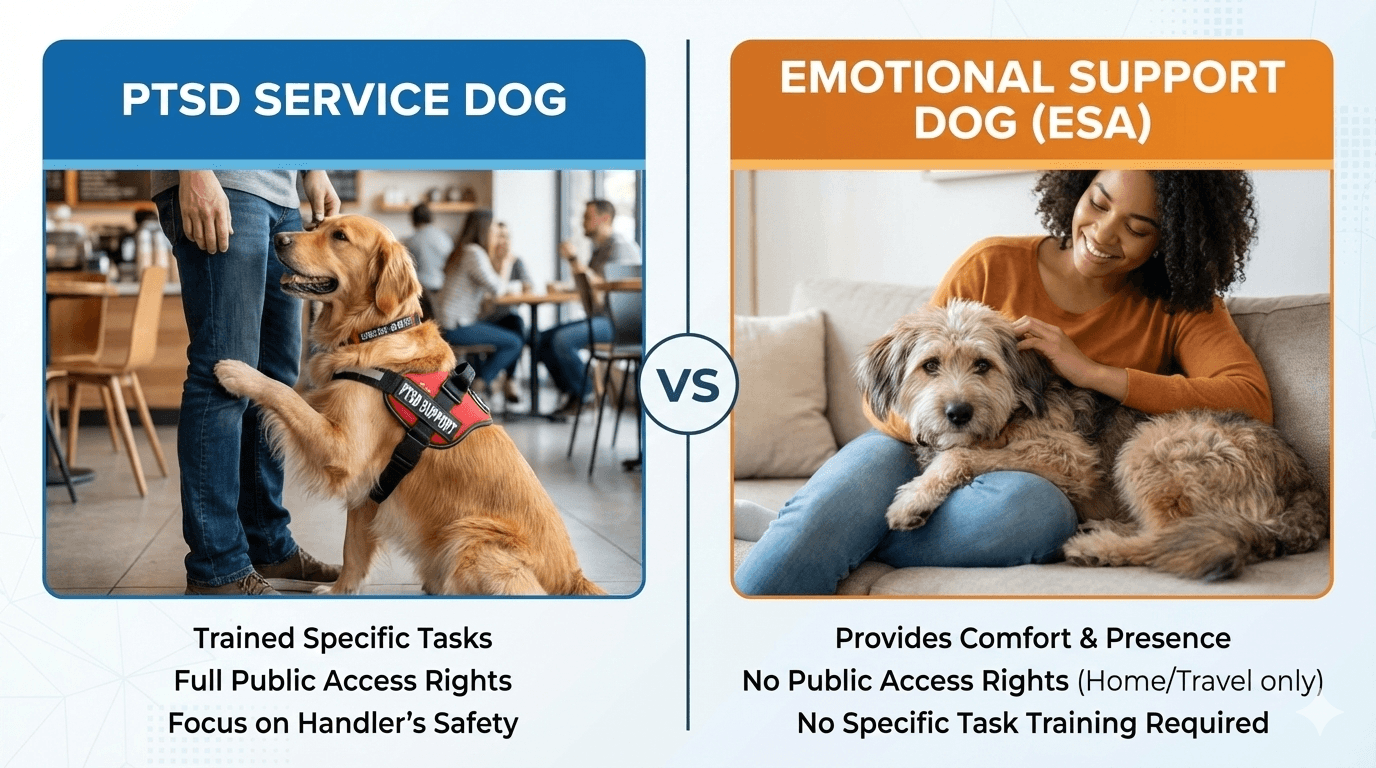

That’s why people often search for phrases like “PTSD emotional support dog” and “PTSD service dog.” Both can be meaningful supports. But they are not the same thing—especially under U.S. law and in real-life access situations.

Here’s the simplest way to understand the difference:

⁃ A PTSD service dog is defined by trained tasks.

⁃ An emotional support dog is defined by emotional comfort and companionship.

And that one word—tasks—is the difference between smoother access, clearer expectations, and fewer stressful confrontations in public.

Quick definitions

PTSD Service Dog

A PTSD service dog is trained to perform specific behaviors that mitigate disability-related symptoms. Those behaviors are not just “nice to have.” They are trained, repeatable, and connected to functional support during PTSD symptoms like panic, dissociation, nightmares, hypervigilance, or shutdown.

A service dog may also be comforting—most are—but comfort alone is not what makes it a service dog.

Emotional Support Dog (ESA)

An emotional support dog provides comfort by being with you. That comfort can be legitimate and powerful. ESAs can help people regulate, leave the house more, sleep better, and feel less alone.

But an ESA is not required to be trained in disability-mitigating tasks. Under the ADA, ESAs do not have public access rights to places like stores, restaurants, or hotels.

Why “tasks” matter in real life (not just on paper)

When PTSD symptoms hit, the hardest part is often that it’s not a logical experience. Your body can react like you’re in danger even when you’re not. In that moment, a task-trained dog can offer structured help that doesn’t require you to “think your way out.”

Tasks matter because they:

- provide predictable support during symptoms

- reduce reliance on other people for immediate help

- can be trained, tested, and proofed for reliability

- separate “my dog comforts me” (valid) from “my dog mitigates my disability” (service dog)

This isn’t about ranking support types. It’s about clarity—so you can choose the right support and know your rights.

What counts as a PTSD service dog task?

A task is more than a helpful habit. It has structure. A PTSD task usually meets these criteria:

1) It’s trained (not accidental)

- Not a task: “My dog stays close when I’m stressed.”

- A task: “My dog performs a trained interruption by nudging my hand until I reorient.”

Natural helpful behaviors can be a starting point, but to become a service dog task, they need training and reliability.

2) It mitigates a disability-related symptom

The task should reduce the impact of PTSD symptoms such as:

- panic attacks

- dissociation or shutdown

- nightmares and night terrors

- hypervigilance and startle response

- avoidance that prevents functioning

3) It’s repeatable and reliable

A task should work across different days and environments—not perfectly, but consistently enough to be meaningful.

4) It has clear “start” and “stop”

Most good tasks have:

- a cue (spoken cue or symptom cue)

- a release (“off,” “all done,” “free”)

- This keeps the behavior calm, safe, and appropriate in public.

PTSD service dog tasks that usually qualify (with real-world examples)

Below are tasks that often meet the standard because they are observable, trainable, and symptom-focused.

Interruption tasks (panic, spirals, dissociation drift)

Your dog is trained to interrupt escalating symptoms in a predictable way—often using a nose nudge, paw target, or sustained nudging pattern.

In real life:

You start scratching, shaking, or zoning out. Your dog performs a trained interruption behavior until you acknowledge and reset.

Deep Pressure Therapy (DPT)

Deep Pressure Therapy (DPT) is trained, calm pressure that helps ground you during panic or shutdown. One simple, ethical training structure is:

calm cue → safe pressure → short hold → clear release → settle

In real life:

You cue DPT early in escalation. The dog applies pressure safely and calmly, then stops cleanly on release.

“Find exit” or “find car” (guided exit)

When decision-making collapses, your dog can guide you to a known safe place: an exit, a quieter area, your car, or a trusted person.

In real life: a store becomes too crowded. You cue “find exit.” Your dog leads you out without you having to plan your route while overwhelmed.

Nightmare interruption / nighttime support

Many PTSD handlers struggle with sleep. Dogs can be trained to:

- nudge to wake you from night distress

- guide you to sit up

- turn on lights (trained switch task)

- bring a grounding item or medication kit (if appropriate)

“Cover” and “block” (creating space in public)

These are calm positioning tasks that help reduce startle triggers:

- cover: dog positions behind you

- block: dog positions in front/side to create a small buffer

Important: this is not guarding. A task-trained dog should remain neutral and controlled.

What usually does not count as a service dog task (even though it helps)

This is where many people get tripped up, because these things are real benefits—but not tasks under the ADA definition.

Usually not considered tasks:

- “He makes me feel calmer” (comfort by presence only)

- “She cuddles me when I’m sad” (without a trained cue/release pattern)

- general good behavior (quiet, friendly, well-behaved)

- wearing a vest or carrying an ID

- protective/guarding behaviors (especially growling, lunging, “watching people”)

A service dog should not behave like a security dog. Calm, neutral, and under control matters.

Rights snapshot: service dogs vs emotional support dogs (high-level)

This is a simplified overview, not legal advice—but it helps set expectations.

Public places (stores, restaurants, hotels)

- Service dogs: generally allowed under ADA when trained and under control

- ESAs: generally not granted public access rights under ADA

Housing

Many people can receive accommodation in housing with either a service dog or an ESA in many situations (rules and documentation expectations can vary). The key idea is that housing operates under different standards than public access.

Air travel

Air travel rules differ and can be more specific. Generally:

- service dogs may be eligible under airline/DOT rules

- ESAs are usually not treated the same as service dogs for flights

When in doubt, focus on what you can confidently say: your dog’s trained tasks and your ability to maintain control in public settings.

The two questions businesses can ask (and how to answer calmly)

In public, staff may ask:

- Is the dog required because of a disability?

- What work or task has the dog been trained to perform?

A smooth PTSD service dog answer sounds like:

- “Yes—he’s trained to interrupt panic symptoms and guide me to an exit.”

- “Yes—she does deep pressure therapy and trained interruption during dissociation.”

Short. Calm. No oversharing.

A simple “task test” you can use at home

Ask yourself:

- Can my dog perform a trained behavior on cue?

- Does it reduce the impact of a PTSD symptom?

- Can it be repeated reliably across locations?

- Can I describe it in one sentence?

- Does my dog stop immediately on release?

If the answers are mostly yes, you’re talking about task work—not just comfort.

Conclusion: comfort is real, but tasks define a service dog

An emotional support dog can be incredibly meaningful. A PTSD service dog can also be incredibly meaningful. The difference isn’t which one is “better.” The difference is what the dog is trained to do, and what that means for public access, expectations, and daily function.

If you’re building a PTSD service dog, focus less on labels and more on:

- calm public behavior

- real task reliability

- clean cues and clean releases

- respectful access etiquette

That’s what protects your rights—and protects the community.