PTSD Service Dog Tasks for Panic Attacks and Anxiety

If you live with PTSD, you already know panic and anxiety don’t always “announce themselves.” Sometimes it’s a slow climb—tight chest, scanning exits, a rising sense that something is about to go wrong. Other times it hits like a wave: your body goes into survival mode before your brain can catch up.

A well-trained psychiatric service dog can help in a very specific way: not by “fixing” PTSD, but by performing trained tasks that interrupt escalation, ground you back into your body, and help you move through the moment safely.

This article is built around the most practical framework I’ve seen work for handlers: a task stack—a simple flow your dog can follow when panic starts:

Interrupt → Ground → Guide → Recover

It’s not a rigid script. It’s a reliable plan your nervous system can borrow when you’re overwhelmed.

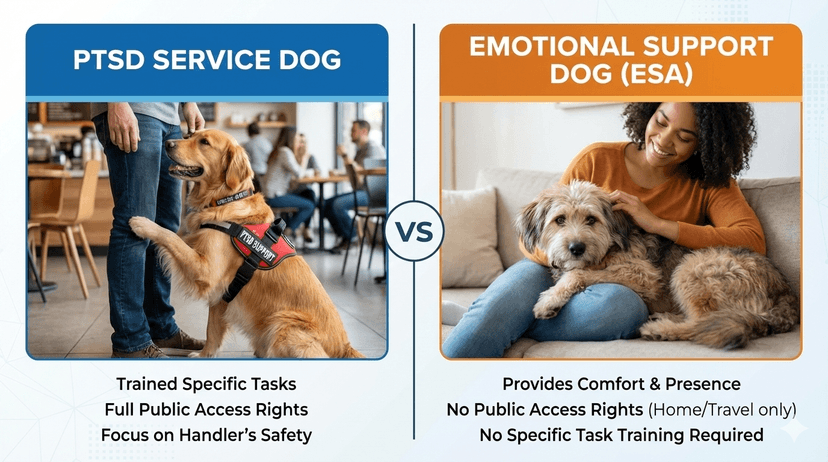

First: what counts as a PTSD service dog task?

Under the ADA, a service dog must be individually trained to do work or perform tasks that mitigate a disability. For PTSD, that means your dog’s behavior needs to be more than comfort-by-presence. Comfort is real and valuable—but legally, the “service dog” part comes from trained action tied to your symptoms.

In real-world terms: a task is something your dog does on purpose, because you trained it, that helps you function during or after an episode.

Examples that commonly qualify include:

- interrupting panic/dissociation with trained nudges or tactile prompts

- deep pressure therapy (DPT) on cue

- guiding you to an exit/seat when you’re overwhelmed

- waking you from nightmares and helping you recover

Why a “task stack” works better than a single trick

Panic is rarely one problem. It’s often a chain reaction:

- thoughts start racing

- the body escalates (breathing, heart rate, tunnel vision)

- decision-making gets harder

- you might freeze, bolt, or dissociate

That’s why a single behavior—like a nudge—can help, but doesn’t always finish the job. A task stack gives you a beginning, middle, and end. Even if the moment is messy, you have a plan to return to.

Step 1: build the foundation (so tasks hold up in public)

Before your dog can reliably help during panic, they need stability—because a stressed dog can’t regulate a stressed human.

This doesn’t mean perfection. It means the basics are strong enough that your dog can stay calm when life gets loud.

The most important foundation skills are:

- a real “settle” (not just lying down, but relaxing)

- loose-leash walking with neutral behavior around people/dogs

- “leave it” and impulse control (food, doors, sudden movement)

- comfort with common environments (parking lots, elevators, carts, automatic doors)

Think of this as building a sturdy floor before you put furniture on it. Tasks are the furniture.

Step 2: train the “Interrupt” layer (catch panic early)

Interruption tasks are your early-warning lever. Their job isn’t to stop every panic attack. Their job is to break the spiral just long enough for you to breathe, orient, or use the next tool.

What interruption looks like when it’s done well

It’s gentle, clear, and repeatable. Not frantic jumping. Not clawing. Not barking at strangers. The dog is simply saying, “Hey—come back to me.”

Common interruption behaviors include:

- nose nudge to hand/leg (often the easiest and cleanest)

- hand target (dog touches your palm, giving your brain something concrete)

- gentle paw tap (stronger input, but must be trained to avoid scratching)

- lick hands (tactile grounding—best as a calm, controlled behavior)

How to train it without making it chaotic

Start in calm moments. Teach the behavior like any other cue, then gradually connect it to your early anxiety signals.

A practical approach:

- Teach the cue (touch, paw, or lick) with rewards

- Build duration (one touch becomes two; then a few seconds)

- Pair with a “pre-panic” context (you do a mild trigger simulation: standing up quickly, putting on shoes, entering a doorway—whatever matches your early pattern)

- Reward calm delivery every time

You’re teaching: “When you notice X, do Y calmly.”

Step 3: add the “Ground” layer (bring the nervous system down)

Once panic starts, the body often needs grounding more than logic. That’s where contact-based tasks can be powerful—especially deep pressure therapy.

Deep Pressure Therapy (DPT) in plain language

DPT is steady, comforting weight and contact that helps many people feel anchored. It’s not magic. It’s nervous system input—like a weighted blanket you can take into the world.

DPT can look different depending on dog size and handler needs:

- small dogs: lap pressure

- medium/large dogs: lean across thighs, chest/torso lean, or side pressure

- public-friendly alternative: chin rest or sustained body lean

Training DPT so it’s safe and predictable

The key is teaching an “on,” a calm stay, and an “off.” That “off” cue matters. It prevents dependency and keeps the dog’s behavior polite and controlled.

A simple progression:

- teach position (“paws up” or “lap”)

- teach “settle” in that position

- build duration gradually

- teach a clear release cue (“off”) and reward it

- practice on different surfaces (couch → chair → bench → quiet café patio)

This is where “human-y” training matters: go slow. Celebrate boring. Calm is the goal.

Step 4: train the “Guide” layer (when your brain can’t choose)

When panic is high, decision-making shrinks. Some handlers describe it like trying to navigate a maze while underwater. Guiding tasks help you move through the environment without needing to “think your way out.”

Useful guiding tasks include:

- find exit (dog leads you toward a known exit/door)

- find seat (dog leads you to a chair/bench)

- forward patterning (dog helps you keep moving when you freeze)

- block/cover (dog positions to create personal space in lines/crowds)

Training tip that makes guide tasks easier

Start with a very predictable “destination.” A specific chair. A specific door. A specific mat. Dogs learn best when “success” is obvious.

Over time, you generalize:

- different chairs

- different doors

- different environments

- mild distractions → real-world distractions

Guiding is often the difference between being trapped in the moment and getting to a place where you can recover.

Step 5: train “Recover” supports (what you need right after)

After panic, a lot of people feel shaky, nauseous, foggy, or drained. Recovery tasks are simple and practical: they help you stabilize without scrambling.

Examples include:

- retrieve a medication pouch (or water bottle)

- retrieve phone (especially if you’re alone)

- go get a partner/caregiver (advanced; only if you have a safe plan)

- settle + sustained contact until breathing normalizes

Recovery tasks aren’t flashy, but they’re the reason many handlers say, “I can get back to life faster now.”

What this looks like in real life

Here are three “human” snapshots of how the stack can play out:

In a grocery line:

Your chest tightens and you start scanning. Your dog nudges your hand (Interrupt). You cue chin rest or light DPT (Ground). If the intensity climbs, you cue “find exit” (Guide). Outside, your dog settles close while you drink water (Recover).

In a parking lot:

You freeze near the car. Your dog paw-taps softly (Interrupt). You cue “forward” (Guide) because moving is the hardest part. Once inside the car, you cue DPT for a minute (Ground), then your dog retrieves your water (Recover).

After a nightmare:

Your dog nudges you awake (Interrupt), stays close while you orient (Ground), and helps you walk to a lighted space if needed (Guide). Then your dog settles nearby until your body feels steady again (Recover).

Public access reality: your dog can be amazing and still have bad days

A service dog must be under control, housebroken, and non-disruptive in public. That’s the standard. But being human also means planning for off days.

Practical handler habits that help:

- bring high-value rewards for difficult environments

- schedule decompression and rest

- keep sessions short when you’re training near triggers

- leave early if your dog is stressed (that’s good handling, not failure)

Common mistakes (and the kinder alternative)

Mistake: Training tasks before basics.

Alternative: Build calm public behavior first—then tasks stick.

Mistake: Accidentally rewarding frantic behavior.

Alternative: Reward calm delivery. If the dog escalates (jumping/scratching), pause and reset.

Mistake: Expecting the dog to “cure” panic.

Alternative: Think “support plan.” Your dog is one pillar, not the whole building.

Mistake: Moving too fast with triggers.

Alternative: Slow proofing wins. The goal is reliability, not speed.

FAQs

Can dogs really detect panic?

Many dogs learn patterns—breathing changes, pacing, fidgeting, posture shifts—especially when trained intentionally. Some handlers also report scent-related sensitivity, but you don’t need that for effective task work.

How long does training take?

Commonly 6–24 months, depending on your dog, your goals, and how often you train. Foundation skills usually take longer than people expect—and that’s normal.

Can a small dog be a PTSD service dog?

Yes, if the dog can perform tasks that mitigate disability symptoms and can handle public access behavior. Small dogs can be excellent at interruption and grounding tasks like chin rest or lap DPT.

Do I need certification or registration?

No official government certification is required for ADA public access. What matters is training and behavior.